Chr. Hansen

Business Strategy and Outlook | by Ioannis Pontikis Updated Jun 27, 2019

From its origins as a cheese rennet producer, Chr. Hansen has transformed into a pioneer in offering microbial and natural color solutions for the food, beverage, and pharmaceutical markets. Our wide economic moat rating is supported by its intangible assets, switching costs, and a cost edge resulting from the company’s years of high research and development, or R&D, spending; strong client relationships; proprietary technology/client data; and leadership position in each of the three markets in which it operates.

Growth is secular and driven mainly by health and wellness trends, including removing undesirable content from food, prolonging products’ shelf life, and improving the taste profile. In food cultures and enzymes, Chr. Hansen’s largest segment (at nearly 60% of sales), the firm holds a dominant position. Price is almost never an essential factor as cultures and enzymes are an insignificant part of end products’ total production cost (less than 2%) while their strategic value to their risk-averse client’s product and core business is asymmetrically higher. This has led to robust pricing/mix contribution.

The health and nutrition division shares a common R&D platform and similar production technology with the cultures and enzymes segment. The human health unit benefits from branded probiotics such as the LGG and BB-12, two of the most documented probiotics worldwide, and an increasingly stringent regulatory environment that should help Chr. Hansen differentiate further from competitors that have less documented probiotic cultures. Similarly, regulation is a significant driver in both plant health and animal health, the other two subdivisions of the segment, with higher utilization of biological nematicides versus chemical alternatives and recent bans on antibiotics in animal feed leading the way.

Lastly, although Chr. Hansen’s natural colors division is the only segment of the group that does not benefit from its fermentation-based research capabilities, it still exhibits healthy returns (25% ROIC over the last decade). Regulation and consumer awareness regarding clean labeling are the main drivers of the conversion to natural colors.

Economic Moat | by Ioannis Pontikis Updated Jun 27, 2019

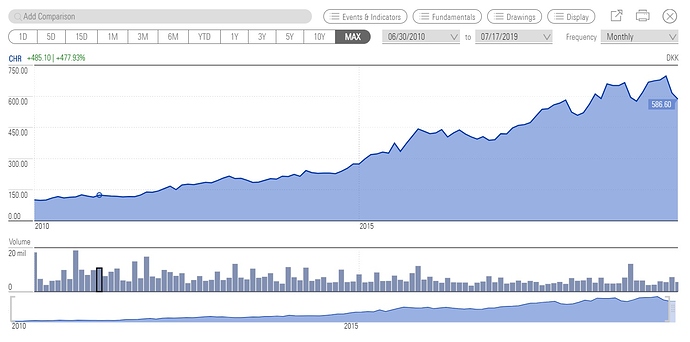

We assign a wide moat rating to Chr. Hansen, supported by its intangible assets, switching costs, and cost advantages. Historically, the company’s return on invested capital has consistently out-earned its cost of capital by a wide margin (close to 30% average return on invested capital, including goodwill versus 7% WACC), a performance we find rare among the consumer staples and flavors and fragrances companies under our coverage. We expect Chr. Hansen to continue generating superior returns on capital for at least the next 20 years with a high level of certainty, consistent with our wide moat rating.

Food cultures and enzymes

We believe the company’s food cultures and enzymes division (59% of sales, 70% of EBIT) benefits from a wide moat. The unit boasts rare returns (45.6% ROIC excluding goodwill in fiscal 2018) and profitability (34.3% EBIT margin in fiscal 2018), producing and supplying cultures, probiotics (20% of sales), and enzymes (20% of sales) for the food industry (particularly fermented milk, cheese, wine, and meat) with a specialization in dairy products such as cheese and yogurt (over 50% of segment sales). Those ingredients determine the main properties of the end product such as taste, texture, nutritional value, shelf life, and health benefits. Manufacturing fermented milk products and cheese requires fermentation of milk by certain microorganisms (bacteria). Over the years Chr. Hansen has built a library of more than 30,000 strains (including through acquisition from partner universities), the most extensive commercially available collection in the world. Each starter culture (combination of different strains of bacteria) used in the manufacturing process of fermented products must be carefully selected based on the item’s unique characteristics, as they impart specific functionalities and properties to the final product. Although Chr. Hansen’s revenue model is limited to the sale of its bacteria-based products, in addition to the ingredients themselves, the firm, as part of its value-added offering, provides crucial added-value services to its clients. These include advice on production process optimization, improving productivity and yields as well as the quality and safety of the manufacturer’s products, ensuring robust application of know-how, and successful integration with the customer’s products and processes.

Chr. Hansen is the dominant player in the broad food cultures and enzymes market globally with an estimated market share of more than 50%. The market for dairy-related items is by far the most significant food culture and enzymes market. The supply side of the market is highly concentrated with the top three players (including Chr. Hansen) controlling more than 80% of the sector (20% for DuPont through Danisco and 10% for DSM), while at the other end, the demand side (global dairy manufacturers) is very fragmented (less than 30% of global dairy product sales come from the top 15 manufacturers according to GlobalData). The division has historically exhibited a rare combination of high top-line growth (9% average organic growth over the last decade), extraordinary returns on invested capital (consistently over 30% over the same period), and best-in-class operating margins (averaged nearly 30% in the same period). We think that a mix of switching costs, strong intangible assets, and a cost edge has helped the division maintain and grow its franchise through a high value-added proposition to its clients.

The challenges and idiosyncrasies involved in the production and distribution of fermented milk products illuminate the low likelihood of Chr. Hansen clients’ switching between different ingredient suppliers. In the first step of the manufacturing process, milk is transferred to the clients’ factory facilities and injected in large vats where it is heated and then cooled to eliminate all microorganisms that may interfere with the controlled fermentation. Once pasteurization is completed, the fermentation process starts with the injection of starter cultures (in the form of frozen or freeze-dried pellets) into the vats. Cultures from disparate suppliers have distinct properties and may require different fermentation times. Depending on the final product, milk type, and starter cultures, 4-20 hours may be needed for the fermentation process to complete. There is an optimal time window (around 10 minutes) during which the fermentation should stop by cooling off the mix. Otherwise, the batch spoils and the fermentation is deemed unsuccessful.

The process carries the risk of virus attacks (phage), which infect the starter cultures (referred to as “starter failures”) and can lead to the same catastrophic results for the dairy operator (consequences range from delayed acidification, changing the quality of the final product, to total batch losses). Sources of contamination span from the starter culture itself to the raw ingredient used (milk, primarily when it is collected from different farms) as well as air/surfaces in the factory. Pathogen attacks are responsible for the highest economic loss at dairy factories since they negatively affect up to 10% of all milk fermentations. Despite considerable effort to address the issue, the industrial use of phage-resistant bacteria could eventually lead to the emergence of phage mutants that are insensitive to current control mechanisms, which necessitates a trusted supplier of cultures with substantial research and development capabilities to stay one step ahead of phage evolution. Given that bacteriophages are extremely host-specific (so certain phage can only infect a few strains of bacteria), Chr. Hansen’s ability to supply its clients with alternative/back-up cultures (culture rotation), sourced from its strong R&D capabilities and largest commercially available strain library in the world, is a crucial feature of its high value-added offering, leading to client intimacy and reluctance from risk-averse dairies to switch suppliers. In addition to pathogen control, cultures and enzymes provided by partners like Chr. Hansen help increase customers’ efficiency and provide considerable implicit and explicit cost savings by reducing the need for certain raw materials in the manufacturing process, such as stabilizers, preservatives, fat, and extra milk proteins for yogurt production (in step with the structural “clean label” trend).

Considering the sensitivity of the fermented product production process as well as the delicacy of the raw materials, Chr. Hansen’s clients are very risk-averse when they pick suppliers of cultures and tend to stick with them unless quality/trust issues arise. Most of the business is transactional (fixed price lists), with longer-term contracts in place for larger clients, but there is no tender business (as in the fragrance and flavor space). Price is almost never an essential factor as cultures and enzymes are an insignificant part of end products’ total production cost (less than 2%) while their strategic value to the client’s product and core business is asymmetrically higher (low cost-to-value ratio). This has led to robust pricing/mix contribution. Chr. Hansen has been able to increase prices for existing products in line with inflation and capture a higher share of their clients’ wallet through new innovative products. This can be accomplished by up-selling to new concept generations and offering new and more uses of its products such as bio protection (increase shelf life naturally). As a result, pricing and innovation have contributed around 4% of the company’s total sales growth over the last five years, which, along with Chr. Hansen’s ability to utilize EUR pricing in emerging markets, is further evidence of robust pricing power.

The importance of Chr. Hansen’s position in its customers’ value chain is further magnified when one considers the impact a problematic fermentation process could have on their business. First, milk is the main raw material used in the production of fermented milk products and accounts for 85% of the total production cost; a failed fermentation could translate into significant costs for the producer. For instance, depending on the price of milk, the size of the vat and the quantity of cultures needed to manufacture yogurt, we estimate that starter cultures costs account for a mid-single-digit percentage of the cost of milk in the vat. Secondly, given that fermentation takes many hours to complete, a bad batch (or failed fermentation) may cause production shortages and unfilled orders, which in turn could damage manufacturers’ relationships with their clients. Since dairy producers’ main clients are retailers/distributors that depend on a high degree of operating leverage to overcome razor-thin margins (volumes drive profits), availability and reliability of temperature-sensitive products on shelves and in the warehouse is critical. Reliability can be a competitive advantage for vendors with a record of timely delivery and consistent quality, as this reduces retailers’ supply-chain risk. Indeed, quantitative evidence confirms our qualitative assessment, with Chr. Hansen’s top 25 customers (around 30% of sales) averaging more than 20 years with the company, implying client incumbency.

We believe Chr. Hansen has built strong intangible assets over the years, supported by its substantial research & development investments (7.3% of sales in fiscal 2017, 5.6% average over the last decade) and unmatched market intelligence capabilities.

Research and development investments have led to more than 2,000 patents granted or pending (including application methodologies and production techniques) and the most extensive commercial library of strains in the world (more than 30,000 strains/isolates, with much of that acquired from research institutions and university laboratories). Strains are bacteria extracted from nature and constitute the building blocks of cultures. Although strains are not unique (similar strains can be found in peers’ libraries as they can be extracted and isolated freely from nature), those that share common properties (phenotype) are collected into building blocks and can then be compounded into cultures optimized for the customer’s product or process. The discovery and documentation of strains are some of the company’s core competencies, the result of years of research and developing spending that is hard to replicate. This strain diversity helps not only in terms of phage robustness (wide portfolio of different cultures with alternatives in case of pathogen attack) in the fermentation process but also in meeting clients’ customized needs.

Equally important, Chr. Hansen has developed an unparalleled market and customer data capability, with an unprecedented 95% of the relevant dairy market mapped (clients’ factory activity, including product lines, production quantities, and cost-in-use data) at the product and country level and 75% down to specific factory level, which helps the company foresee clients’ needs and provide a reliable tool to extract insights regarding recent market trends as well as new opportunities. This unique dataset that Chr. Hansen has amassed over the years showcases the ingrained position of the firm in its clients’ value chain and further adds to customer captivity. Indeed, in some cases Chr. Hansen has installed sensors in its smaller clients’ fermentation equipment to ensure adequate monitoring and smooth integration of the firm’s ingredient solutions, such as identifying the optimal time to stop the fermentation process (pH measurement).

Further, this granular mapping of clients’ operating activity (dairy product volume, culture volume, product mix, and product technology) enables the company to more efficiently utilize its finite resources (sales, service, R&D) in the direction of its customer-specific needs. We think that this information asymmetry (Chr. Hansen knows its clients’ operations and future needs much better than any competitor ever will) disincentivizes both incumbents and potential new entrants from entering Chr. Hansen’s turf, creating high barriers to entry as market data of that caliber (depth and breadth) on the dairy industry are scarce (highly fragmented industry with thousands of producers worldwide).

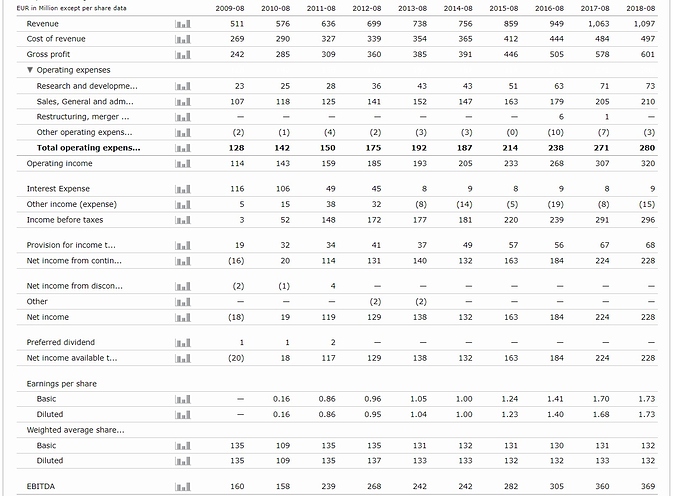

Lastly, Chr. Hansen’s ability to economically produce cultures and enzymes on an industrial scale contributes to its wide moat. Despite the fact that no pure-play comparables exist for benchmarking purposes as both DowDuPont and DSM are conglomerates with many different segments (broad ingredient solutions across the food and industrial applications spectrum) under their group umbrella, we think that the firm’s dominant position in this niche but global market (more than 50% market share), coupled with the favorable economics underpinning large-scale production of bacterial cultures, ensures that Chr. Hansen maintains a moatworthy cost edge versus peers. With some 50% of the total production cost being fixed or semi-fixed (wages, equipment, and infrastructure maintenance), 25% devoted to utilities (energy) and the residual 25% spent on raw materials such as water, sugar, vitamins, and trace minerals (nutrients for growing bacteria), operating leverage is significant. This ensures that each additional batch of cultures produced by the same production facility carries a progressively lower marginal cost as a consequence of economies of scale and elevated capacity utilization. Indeed, over the last 12 years, Chr. Hansen has improved underlying operating margins by 10 percentage points to 29% in fiscal 2018 (from 19% in fiscal 2007), primarily driven by increased production efficiencies and higher capacity utilization (plus 150% sales growth versus plus 185% gross profit growth since 2007) as well as lower discretionary or indirect expenses (sales, marketing, and admin) as a percentage of sales (to 19% from 22% excluding research and development expenditures). This is evidence of operating leverage in the business supported both by economies of scope (costs for R&D, sales, applications, and service teams are spread across an extensive range of products and end markets) and economies of scale (high volumes drive greater manufacturing profitability).

Human and nutrition

The second most important unit of the company (21% of sales and 22% of EBIT) is the human and nutrition business, which we think benefits from a wide moat as well. The business operates in three markets: the human health (50% of segment sales by our estimates), animal health (45% of the segment’s sales according to our estimates), and plant health markets (likely around 5% of segment sales). The division develops and sells products with a documented health effect (probiotic cultures) for the dietary supplement, over-the-counter pharmaceutical, infant formula, animal feed, and plant protection industries. It shares moat-enhancing resources (research and development, production facilities) with the cultures and enzymes division, leading to strong profitability (31% EBIT margin in fiscal 2018) and returns (29% ROIC excluding goodwill).

Apart from the aforementioned sources of competitive advantages, the human health unit benefits from branded probiotics (trademark strategy) such as the LGG and BB-12, two of the most documented probiotics worldwide (LGG has more than 1,000 scientific publications, close to 5 times more than other leading probiotic strains), and an increasingly stringent regulatory environment for probiotics, which should help Chr. Hansen differentiate further from competitors with less documented probiotic cultures. The division focuses on developing products based on probiotic cultures for the dietary supplements and special nutrition markets and is the leader in the probiotic supplements sphere, selling to a broad range of clients, including pharmaceutical companies for use in their branded, over-the-counter supplements. Trademarked ingredients are clearly labeled in the final products and allow price premiums (since those probiotics are only found in the premium end of the market), and a potential change of supplier by the manufacturer would effectively result in an entirely new product, considering loyal consumers’ awareness of ingredients’ properties and documented health claims. Most importantly, however, the probiotic strain/product has to be alive and consumed in accurate doses to be effective. Probiotic product shelf life (stability) decreases with high humidity, high temperatures, and contact with air, so strict production quality control standards as well as reliable dosage forms (that deliver an accurate quantity of product that has proven efficacious in clinical trials) and packaging are critical to ensure ideal conditions for stability and effectiveness. For example, Chr. Hansen always guarantees two-year stability at room temperature and a market-leading three years at 30 degrees Celsius for some products. Chr. Hansen’s long-standing track record of consistent, high-quality delivery, extensive experience with the products it offers, and deep understanding of the items it sells (borne of its class-leading research and development capabilities) makes it a trusted partner for clients that require a steady supply of these delicate ingredients. Hence, we think client stickiness is very high in that division.

In animal health, which includes ingredients for the animal feed market (beef, swine, and poultry as well as silage inoculants), Chr. Hansen boasts a leading aggregated market share, though the company may not be the largest supplier in each of those component markets. The addition of probiotics with well-documented health claims in the animal health space can increase production efficiencies and limit production losses for growers, while at the same time reduce the need for antibiotic growth promoters. Regulation is a crucial driver of growth in the animal feed space, with recent bans on antibiotics creating opportunities for incumbent and new players. Here again, the company tries to differentiate its offering from competition through documentation (product performance claims, economic benefit); many of the strains it utilizes for animal health products are the most documented on the market (for example, the BioPlus YC swine probiotic). We think this subdivision benefits for the same sources of competitive advantages as the human health division: switching costs, cost advantages, and intangible assets. Once Chr. Hansen has identified which strains should be utilized for each client’s specific need or challenge, it runs trials on animals to assess the impact on the production parameters (test the efficacy of the product). Clients are growers, that are typically risk-averse and looking for the right solution to increase productivity while at the same time limit harmful bacterial infections that can cause a severe economic loss (for example, increasing pig performance on lower-energy diets, thus reducing feed costs without reducing yield, or maintaining healthy microbial diversity in turkeys’ guts to limit infections). Thus, we think that once clients start adding Chr. Hansen’s animal probiotic products in their animal feed, there is little incentive to switch to another supplier.

Plant health, the third part of the division, while still small (EUR 10 million sales, but targeted to reach EUR 100 million by 2025), commands a leading market position in sugar cane crop protection in Brazil, a market that is still in its infancy. The segment is the result of Chr. Hansen’s strategic alliance with FMC Corporation, covering development and commercialization of biological products, that commenced in October 2013. In the partnership, FMC, a traditional chemical plant solutions provider, offers its global market access, formulation capabilities, field trials, and registration/commercialization experience while Chr. Hansen provides its expertise in producing stabilizing (agrochemicals need long shelf life at poorly controlled temperatures) bacteria at scale and its world-class microbial application know-how. We think the business benefits from switching costs and cost advantages (due to shared production and research capabilities with the rest of the company). Unlike prevention-oriented health solutions, clients (farmers, crop growers) in this business are more likely to appreciate the product’s added value by being able to see the improvement of their crop yields and quality firsthand (less than 5% of the final product’s cost). Also, Chr. Hansen’s capacity and best-in-class fermentation production processes should ensure consistent manufacturing efficiencies as volume grows. Stricter regulation (for example, Furadan, the leading chemical sugar cane nematicide in Brazil, was taken off the market in 2018) creates barriers to entry and accelerates the transition to higher utilization of biological nematicides versus chemical alternatives. Competition is focused on the soybean and corn markets (Novozymes is the leader in that space), giving Chr. Hansen room to build its standing.

Natural Colors

The natural colors division (20% of sales and 8% of EBIT) is the only segment of the group that does not benefit from the fermentation-based research capabilities and production facilities of the rest of the organization. Still, we think the unit benefits from a narrow economic moat, supported again by cost advantages, intangible assets, and switching costs; this view is consistent with the segment’s more than satisfactory ROIC over the last decade (25%). The division extracts and produces color pigments from natural sources such as berries, roots, and seeds as well as coloring foodstuffs that are processed from edible, natural sources such as fruit and vegetables and cater to food manufacturers with applications in confectionery, ice cream, dairy and fruit preparation, prepared foods, and beverages. The sector is composed of five main players (including Chr. Hansen) with similar market shares, with Naturex and Sensient along with Chr. Hansen operating at a global scale with a broad product offering. Food coloring is essential for manufacturers and retailers because it not only enhances colors that occur naturally but also makes food more attractive (products’ appearance is also informative, as consumers can more easily identify vividly hued products on sight). Currently, the food colors market’s size is around EUR 1 billion, with natural varieties accounting for almost half of the value market share but still only 35% of the volume share. This can be explained by the fact that synthetic colors cost less than their natural alternatives (1% versus 3%-5% of the end product cost respectively).

Regulation and consumer awareness regarding clean labeling are the main drivers of the conversion to natural colors, while the ability to cater to clients globally with a wide range of products (full range of shades to match the flavor profile of the product and a variety of coloring foodstuffs) is a differentiating factor for large players. The health and wellness consumer trend, along with the findings of the so-called Southampton Study (published in a well renowned medical journal, the Lancet, in 2007, the article linked some synthetic colors to hyperactivity in children), has lifted consumer awareness of the sources of food colors. In addition, regulatory authorities are tightening labeling requirements, especially in Europe (with regulation already in place for certain artificial colors), with natural varieties’ conversion volume now at 60% versus 25% in North and Latin America (while there is no regulation in the U.S., artificial colors are under review in Latin America) and 30% in Asia and Pacific (Indonesia and Vietnam have banned artificial colors in some categories). Natural pigments are less stable and more sensitive than artificial alternatives and require a great deal of expertise in the regulatory, application and technical aspects of the business, which we think benefits large established players with significant experience in dealing with those issues. Once manufacturers or retailers pledge to utilize natural colors in certain categories of their products, there are only a handful of dedicated suppliers that can cater to their specialized needs. The stability of the hue, the degree of interference with the product’s taste, temperature storage requirements, and compatibility when blending new shades are some of the intricacies that manufacturers face in the application and formulation process, which, if navigated correctly, can lead to tangible cost savings (for instance less scrap because of fading or less use of expensive bottles with UV filters to protect appearance). Vendors also provide guidance on navigating for different regulatory frameworks (such as labeling that is free of “E” numbers in Europe).

Risk and Uncertainty | by Ioannis Pontikis Updated Jun 27, 2019

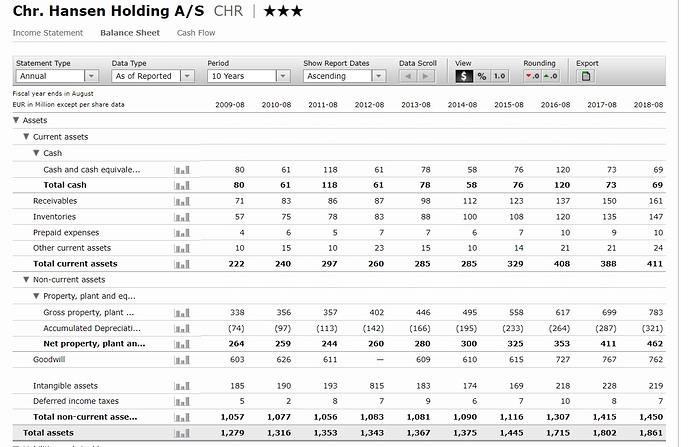

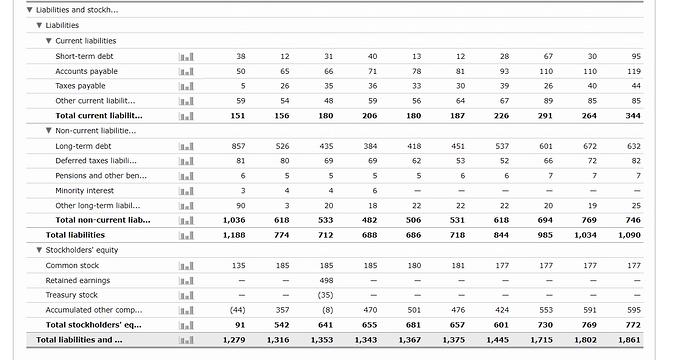

We assign a low uncertainty rating to Chr. Hansen, based on the limited cyclicality of the business, moderate financial leverage, and high operating margins that provide a buffer against earnings shocks.

The firm’s customers are mostly in noncyclical industries like food, beverage, and pharmaceuticals, though its agricultural clients have their own commodity cycle, which is distinct from the economic cycle. Chr. Hansen’s natural colors business is the most sensitive to the commodity cycle, and it might not always be possible to recover increases in input costs from customers.

There is a low risk of business being lost, given high customer-switching costs that tend to make the business sticky. The largest 25 clients account for around one third of sales, so the customer base is highly fragmented, suggesting that business risk is low. Further, the cost of cultures and enzymes accounts for a very low percentage of a customer’s final product cost, which is negligible relative to the strategic value.

Chr. Hansen’s growth depends on its customers’ innovation pace and expansion rates, as well as secular health and wellness trends, which are fundamental drivers of sales and earnings for ingredients companies. If these growth rates slow or secular trends weaken, there will be a negative knock-on effect on the company’s growth prospects. Risk also arises from the potential for regulatory changes that might hurt demand for its products or increase the cost of doing business, although stricter regulation has been a fundamental driver of growth for Chr. Hansen and especially its Health and Nutrition and Natural Colors segments.

Chr. Hansen has limited currency risk. Although its global operations entail currency risk (both transactional and translational), the company uses euro-based price lists, which means if a currency depreciates against the euro (the reporting currency for the firm), local currency prices will automatically be increased.