De disculpas nada .Aquí todo debate sin insultar ni faltar al respeto es bienvenido. El debate te hace ver la luz . Gracias a Vd. por participar

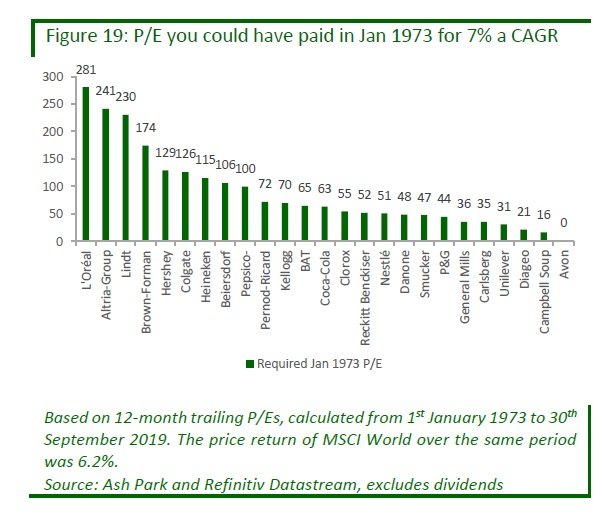

Obviamente, survival bias, etc. Pero en 1973 casi todas esas empresas ya eran blue chips y estaban entre las mayores empresas de sus respectivos países.

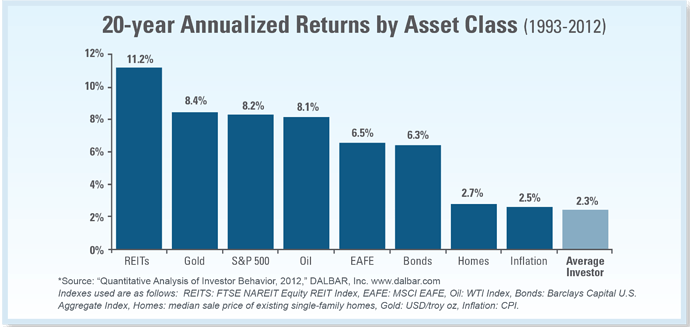

Ojo al leer la letra pequeña, que se trata del inversor medio en fondos. Planes de pensiones (privados), y gente como Vd mismo que o como unos cuantos más que hemos venido invirtiendo en acciones no estaríamos ahí (lo que no quiere decir nada en cuanto a resultados)

Tiene Vd. razón . El inversor medio en acciones,le fué parecido.

“rentabilidades pasadas no garantizan rentabilidades futuras” … a veces,estas últimas són hasta peores (se puede añadir)

Ya le explique lo de mi buena estrella con una acción que tengo desde hace 20 años. A pesar de que esta empresa reinvierte o guarda más del 80% del FCF, no vea lo que supone y el gusto que da que aún así, esa empresa te paga como 5 veces la inversión inicial en dividendos todos los años.

PD: que conste tampoco me ha hecho rico, la inversión inicial era muy pequeña.

Y que empresa es,si se puede preguntar ?

No cotiza, se lo comentaré personalmente porque me consta que usted la conoce

Querido amigo,

A ver si me puede echar una mano para resolver estas dudas sinceras que me asaltan.

Que es una compounder?

Que periodo de tiempo hace falta para saber que una empresa es compounder?

Una empresa que recorta el dividendo deja de ser compounder?

Una empresa de private equity como KKR es compounder?

Que criterio usaríamos en ese caso para decir que es o no compounder?

Si Buffett o Akre son los paradigmas de las compounders…todo lo que compran son compounders?

Si muchos de los aparentemente sesudos estudios como el que ha tenido a bien señalar @AlanTuring, son en muchos casos cuanto menos cuestionables por su veracidad, podemos saber que las historias de Buyandhold o la abuelita forrada, son veraces? Lo sabemos o simplemente lo queremos creer?

Creo que ambos nos conocemos bien y sabemos que compartimos nuestro gusto por las empresas que componen, pero un servidor se plantea, si viendo la cartera de Akre, por ejemplo, mucha gente denominaría sus compañías compounders ex ante.

Al final, a todos nos gusta lo mismo. Comprar compañías que suban su cotización y si además reparten viruta por el camino, pues miel sobre hojuelas. Todo el resto pues como bien apunta es la filosofía de cada uno, todas respetables, eso si.

“Para tener una vida sana hay que comer bien y tener actividad física moderada”, sería algo que yo creo que todos compartimos. Ahora bien, que es comer bien?

A mi abuela diabética, hace algo más de treinta años le prohibieron comer cosas que hoy en día se aceptan como saludables para su dolencia, haciendo mucho peor sus últimos años de vida. Cosas que comemos hoy probablemente se verán con otro prisma dentro de treinta años más.

Con todo esto quiero decir que yo pienso que la inversión es todo menos fácil, y que los que somos respetados en la Comunidad +D, entre los que le incluyo, pues yo mismo le profeso una gran admiración, deberíamos medir los mensajes que lanzamos a los novicios que se acercan a la inversión. Y se lo dice alguien con una cartera pública, que este año le ha ido fenomenal. Cualquiera de los que hayamos comprado pepinos durante los últimos diez años y los hayamos mantenido, hemos ganado cantidades nada despreciables. Lo que nos depararán los diez años siguientes, honestamente no creo que sea igual.

Y ojo, recalco antes de que me lo digan, que pueden aplicar lo mismo a la inversión cuantitativa o cualquier otra.

Uno de los valores que intentamos inculcar en +D, es que la gente debe hacer sus deberes, pues lo más probable es que cualquiera que compre acciones de XXX y se eche a dormir, tiene posibilidades de forrarse a treinta años vista o a quedarse en pelotas, y eso es algo que no libra a ninguna compañia. Repito … a ninguna.

No hay pueblo que no se haya, creído el pueblo elegido.

El peligro es que alguien piense que esto es fácil, yo he pensado lo mismo que usted @jvas, pero se deben hacer los deberes como bien dice. Quien no lo haga lo pagará, y quien lea este hilo entero verá que de fácil no tiene nada. Empezando por asumir de verdad el largo plazo…

Por cierto deberían cumplir lo que prometieron, el podcast con DanGates, Xiscomartorell y Quixote1, estuvo la mar de entretenido

D. @jvas . esas preguntas que se (me ) hace ,son las que me hago casi todos los días. Por lo que me temo que voy a ser de poca ayuda.

Una compounder no deja de ser un buen negocio con visibilidad a largo plazo.

Para mi ,el dividendo es un factor secundario .Si puede componer sin repartir (como BRK.b, MKL) ,para mi mejor,mas sencillo.

No hacer nada:Estoy de acuerdo. Hablando con propiedad ,lo correcto sería hablar de baja rotación. Replantearse la mejor inversion posible (por defecto) ,cada vez que se añade capital es lo más sensato (EMHO)

Que buyandhold2012 puede no ser real ,por supuesto. Como muchos de los foreros que pululan por aquí. La falsedad, no solo (pe) se dió en SOCHI (con los controles antidoping más estrictos de la historia olímpica) , en el mundo digital es lo habitual.

Buffett,Akre,Russo,Carret,Rochon, Terry Smith …fuentes de inspiración .Aqui esta todo inventado.

Desinformación al inversor que esta comenzando : No puedo estar mas de acuerdo. A veces ,el tono desenfadado , con innecesaria ironía , puede dar una impresión errónea. Esto es complejo. Lo importante es encontrar un estilo de inversión que se ajuste a cada uno (y no al revés) .

Cuanto mas se lea ,cuanto mas sepa uno de negocios,contabilidad ,recursos humanos;mejor. Esto es un acopio de información que abarca toda una vida. De las pocas cosas en que la edad aporta valor.

No es fácil . Aquí los errores se pagan con pérdida permanente de capital . Hay empresas que no recuperan ,mercados bajistas en los que es fácil sucumbir al pánico y vender bien abajo.

No obstante ,el riesgo esta en todos lados. Los depósitos se requisan,las monedas se devalúan, los bonos no pagan el principal, uno de los mejores bancos del mundo (hace 10-20 años) se vendió por un euro.

No, no es fácil.Sobre todo ,cuando uno no sabe, lo que se trae entre manos.

Esto para mi es un camino incompleto:como dice Munger ;solo con lo que sabes ahora, no llegarás muy lejos en la vida.

Un placer,leerle D. José . Gracias por aportar.

Ante las dudas existenciales planteadas últimamente en este foro sobre que es una acción compounder y si realmente existen o son una mera entelequia, les dejo esta interesante entrevista, a mi modo de ver, que puede arrojar luz sobre el asunto.

Interview With Eric Schoenstein of Jensen Investment Management

The Motley Fool sits down with a growth investor.

Motley Fool Staff

Jun 3, 2016 at 12:45PM

Jensen Investment Management — in Lake Oswego, Ore., about as far as you can get from Wall Street — is driven by its commitment to investing in high-quality businesses at reasonable prices. The firm’s successful strategy of investing only in companies that have generated a return on equity (ROE) of at least 15% every year for the past 10 years hasn’t changed in more than a quarter-century.

The Jensen Quality Growth Fund has a five-star rating from Morningstar, and its risk-adjusted returns were better than 95% of its peers’, the S&P 500, the Russell 1000 Growth Index, and the Morningstar Wide Moat Index during the market cycle from the previous peak in October 2007 through February 2016. Looking back even further, since 1993, the fund’s risk-adjusted returns outperformed 90% of its peers, as well as the S&P 500 and the Russell 1000. The fund has more than $5 billion in assets under management and 25 holdings. The portfolio’s average return on equity is about 28%, and the fund’s 10-year average turnover is 14%, which implies an average holding period of about seven years.

Eric Schoenstein is a managing director and portfolio manager for the Jensen Quality Growth Fund. He’s also chairman of the firm’s investment committee and coordinates the fundamental research across Jensen’s investment team. Motley Fool analyst John Rotonti interviewed him about finding great investments, when to sell stocks, and more.

John Rotonti: How do you define a high-quality business ?

Eric Schoenstein: A high-quality business is one that has real and durable competitive advantages, a strong balance sheet, high and/or growing market share, robust free cash flows, opportunities to reinvest the free cash flows into growth, and a capital allocation policy focused on generating long-term shareholder value.

John Rotonti: How do you define a high-quality management team ?

Eric Schoenstein: In almost all cases, we visit with management in person before making an investment. We evaluate a management team by trying to determine if it is doing what’s best for the long-term health of the business and its owners. We want to get a sense of who they are, why they are passionate about the business, and what the corporate culture is like. It’s often easier to do that in person than over the phone. In these meetings, we’re not interested in quarterly estimates. Rather, we are focused on management’s five-year strategic plan, capital allocation priorities, opportunities to reinvest at high rates of return, the legacy they want to leave, and how they think about value creation.

John Rotonti: How do you narrow the pool of companies you want to invest in, and how big is that pool for the Quality Growth Fund?

Eric Schoenstein: The firm’s investment strategy has not materially changed in our nearly 28-year history. We just try to get better at it over time. Our initial filter screens all companies based in the U.S. with a market cap of at least $1 billion. So we are pretty much size- and sector- agnostic. This results in a list of about 4,000 companies. From there, the fund is only allowed to invest in companies that have generated a return on equity of at least 15%, as calculated by the Jensen investment team, in every single year for the last 10 years. Today, that screen provides us with an investable universe of about 220 companies. That is the pond that we fish in. Then our job is to find the most attractive fish in that pond. So we must do some work on each of those 220 businesses, which we end up narrowing down to 60 to 80, which is our core investable universe.

Our 15% ROE hurdle for the last 10 consecutive years is non-negotiable because consistently high ROE is an indicator of competitive advantage and consistent value creation. Companies that generate high ROE also tend to generate strong earnings and free cash flow to reinvest in growth, strengthen the competitive position, and return cash to shareholders. We believe companies generating high ROE can compound value creation at higher rates, and over time the share price should follow, often with less volatility. We use 10 years because it more likely shows which companies can generate high returns over a full market cycle — in other words, in both good and bad economic environments.

As the Jensen Quality Growth Fund name implies, we are ultimately looking for companies with a strong quality foundation and the ability to grow profitably over time.

John Rotonti: Why do you focus on ROE as opposed to other common performance metrics, such as return on invested capital (ROIC) or return on assets (ROA)?

Eric Schoenstein: The most straightforward answer is that ROE can be easily calculated and screened for across an entire universe of companies. But ROE is just the invitation in the door. Once they are in the door all those other measures become part of the due diligence process. In some circumstances ROE is higher than ROIC because of debt. We scrutinize a company’s debt level closely. We do not shy away from debt, but we want to make sure that the companies we invest in do not need debt to operate, but rather strategically use debt to grow shareholder value.

John Rotonti: In your opinion, is one source of competitive advantage stronger and more enduring than another?

Eric Schoenstein: Every business that we invest in has its own unique advantages, but we don’t favor one particular advantage over another. For us it’s about identifying a real advantage, having confidence in the durability of that advantage, and investing alongside management teams that are doing a good job of investing to protect the firm’s competitive advantages.

John Rotonti: How do you define a growth company?

Eric Schoenstein: We look for growth of revenue, earnings, free cash flow per share, market opportunity, etc. The mix we look for will be different for each company and industry. In this current slow-growth environment we are paying particularly close attention to organic revenue growth.

John Rotonti: Would you rather invest in a company that is reinvesting 100% of earnings into growth (or at least almost all of its earnings) or one that can both grow and return cash to shareholders through dividends and buybacks?

Eric Schoenstein: It depends on where the company is in its growth cycle. Some younger businesses have the opportunity to reinvest all cash back into growth at high rate of returns. But remember that we need 10 years of high returns before we can invest. Most of the companies that we invest in have such high free cash flows that they can maintain a strong balance sheet, invest in growth, and pay a dividend and/or buy back stock. So our investments have the ability to do it all and it’s managements job to balance and prioritize between them. We like dividends because there are periods when the market doesn’t cooperate, but the dividend allows us to generate some return on our investment while we wait. We also like dividends because it is a commitment. We all know how the market responds to a dividend cut or suspension. Dividends are different from buybacks in this regard.

John Rotonti: How do you come up with an estimate of intrinsic value?

Eric Schoenstein: We look at valuation from different perspectives, but our primary valuation tool is discounted cash flow analysis, and we discount those cash flows using two different discount rates. In the first case, we use the same discount rate across our entire universe, which in effect is similar to an internal rate of return. One component of this is the risk-free rate. We don’t normally use the 10-year or 30-year U.S. government bond. Instead we use an interpolated 20-year rate and the 2-year moving average of the 20-year rate, which adjusts for the current environment and dampens some of the volatility. Given historically low interest rates, today the discount rate that we are using across our universe is about 8%.

In a second scenario, we use data from Duff & Phelps to calculate a unique discount rate for each company in our universe. We have higher conviction when the share price looks undervalued using both approaches as opposed only one or the other.

We then check our thinking using valuation multiples, as well as other metrics. Given that we focus on free cash flow more than reported earnings, we tend to favor cash-flow oriented multiples.

John Rotonti: What common characteristics or patterns do you recognize in your winners?

Eric Schoenstein: The quality characteristics that I mentioned at the beginning all show up in our winners, but the single most important thing is the consistent historical performance. Our research and portfolio returns indicate that consistency in the past leads to a higher likelihood of persistency in the future. This leads us to be very patient, long-term holders. We currently have 25 companies in the fund and nine of those have been in the fund for 12 years or more. The hallmark of the companies that we invest in is that they reinvest their cash flows at high rates of return which leads to compounding of value over time, assuming the rate of return is above cost of capital.

John Rotonti: What have you learned from your losers?

Eric Schoenstein: The biggest challenge for a high-conviction, concentrated, long-term oriented manager is to know when the tide may have turned and when to get out. In the previous question we talked about patience. But it is not blind patience. We must monitor our holdings diligently and be willing to exit the position when our analysis tells us to do so. We do post mortems every time we sell a position and try to learn from both our winners and our losers.

John Rotonti: Are there any industries you tend to prefer — or avoid?

Eric Schoenstein: We try to identify companies with competitive advantages and consistently high returns and free cash flow across cycles. So we have historically not invested in utilities or energy. They just have a difficult time meeting our quality criteria. ROE at utilities is regulated so they don’t meet our ROE requirement. Energy companies are dependent on commodity prices so they do not control their own destiny and their returns and free cash flows are very inconsistent.

The big four that we focus on are consumer staples (which are supported by strong brands), healthcare (supported by patents), global industrials (benefits from global scale), and technology (which may have network effects, scale, or high switching costs).

John Rotonti: Do you have any performance metrics that you prefer management compensation be based on?

Eric Schoenstein: We prefer compensation based on the performance and growth of the underlying business rather than stock price performance. If the business performs well, the stock price should follow.

John Rotonti: When do you sell?

Eric Schoenstein: We sell if (1) the company fails to meet our ROE requirement, (2) the shares become overvalued, or (3) we want to exit a lower quality company and invest the funds into a higher-quality opportunity from our bench.

We have a seven-member investment team and we require consensus on all buy and sell decisions. This may sound like a high hurdle, but remember that we are very long-term holders so we get to know the businesses, industries, and management teams very well over time. So for sell decisions there is usually a clear deterioration in competitive position (business quality) or clear over-valuation. And, of course, if the company fails to generate a 15% return on average equity in any year, then we must sell, so that case is easy. Incidentally, we do very little selling for breaking the ROE rule because companies that have a long history of doing well tend to do well going forward. We continue to believe that consistency leads to persistency.

We monitor our watch list or bench of high-quality companies very closely, so for buy decisions there is generally a clear consensus on under-valuation.

John Rotonti: How do you think about portfolio diversification?

Eric Schoenstein: In the fund, no single position can grow larger than 7.5%. We also have a 30% cap on any one sector. But below that we are really focusing on diversification by industry. So, for example, we own both Microsoft (NASDAQ: MSFT) and MasterCard (NYSE: MA). They are clearly not in the same industry, but both fall under the technology sector.

John Rotonti: Can you discuss the research process at Jensen Investment Management?

Eric Schoenstein: Each of the seven members of the team is a portfolio manager. We are predominately generalists, but some of us are more comfortable with some industries over others. Four of the seven are assigned primary coverage of companies, both current holdings and names on our bench. The other three have other firm-related responsibilities such as meeting with our large investors. Those four analyst/PMs cover between 15 to 20 companies each. So our core universe of current holdings and top new ideas is about 60 to 80 names. So, we do extensive research to narrow 220 companies down to only 60 to 80 of the highest-quality/highest-conviction ideas and that becomes our core investable universe. We meet as a team on a daily basis to discuss holdings and updates. All of our research is performed in-house.

Muy interesante, gracias.

Quizá el único matiz sea el margen de 10 años para coger un ciclo completo, estos últimos 10 han salido algo positivos…

Tiene usted toda razón. En mi humilde opinión, esta entrevista hay que tomarla como una aproximación al concepto de las compounder, nada mas, al final un filtro solo es una forma de centrarse en el estudio de determinadas empresas, ahí es donde empieza el estudio de verdad y donde los números empiezan a perder importancia y tiene más el sentido común y la inteligencia emocional para detectar determinadas situaciones: marca, exclusividad, situaciones oligopolisticas, grandes gestores de capital, margen de crecimiento en tu sector… . Al final, la contabilidad es sólo una parte de este arte y, en mi opinión, es la parte más sencilla ya que si no todos los contables serían millonarios.

Hola @thinkoutsidethebox, gracias por subir la entrevista.

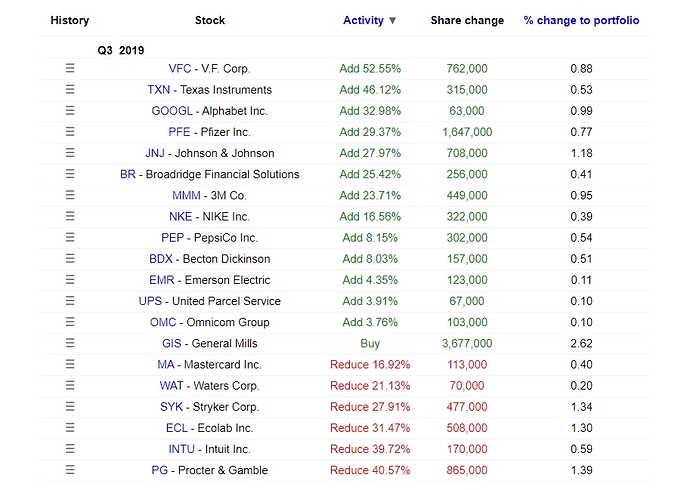

$JENIX es precisamente un fondo de inversión que sí vende. O más concretamente rebalancea desde las compounders de moda hacia aquellas que, teniendo también un futuro prometedor, están pasando por problemas temporales.

Los movimientos del Q3 por ejemplo:

Ni que decir tiene que para llevar a cabo esta tarea con éxito hay que hacer algo más que calcular el ROE del último ciclo económico.

Saludos

Muchas gracias por su aportación Don @Helm. Siempre un placer leerle por el valor de todas sus aportaciones. Entrando en materia, claro que los de Jensen rebalancean. Ellos mismos lo explican en su entrevista y luego se ve reflejado con los movimientos del último trimestre, que usted muy amable nos ha aportado.

Para mi el valor de la entrevista es la aproximación al concepto de las compounders, sobretodo ante las ciertas dudas metafísicas/existenciales de si este tipo de acciones son una entelequia o no. Luego, en cuanto al nivel de rotación, cada maestrillo tiene su librillo, a unos les gustara rotar más y a otros menos. Como ya he explicado en otras ocasiones, no creo que nadie en su sano juicio piense que nunca y bajo ninguna circunstancia haya que rotar, aunque yo soy del gusto de rotar poco para dejar que los buenos negocios alcancen su verdadero valor. Fíjese que si no usted puede vender Apple, por poner un ejemplo, a 200 y perderse más de un 40% de su subida para comprar una acción que supuestamente va ir mucho mejor y no lo hace nunca.

Como he manifestado en otras ocasiones, cuando participas en la carrera de relevos, puedes ir más rápido, pero también te expones a que se te caiga el testigo.

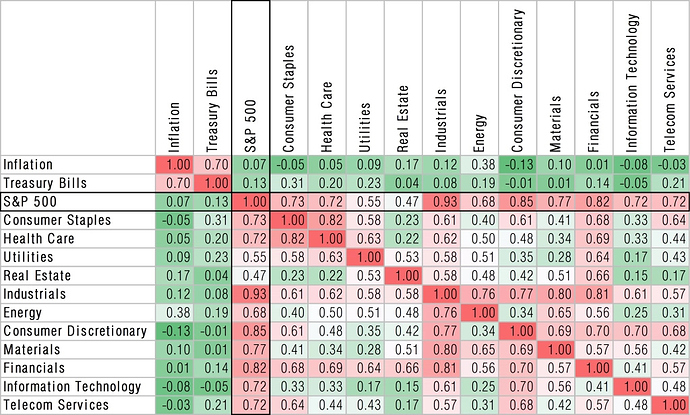

Aquí tiene un gráfico que alguna vez hemos puesto. Entre la maraña del gráfico y aunque las probabilidades en principio serían a favor de ciertos sectores , para el periodo considerado, nada garantiza que un inversor particular no obtuviera mejores resultados en épocas largas estando en sectores en teoría menos rentables.

Luego está en la habilidad del mercado para poner a prueba las convicciones de un inversor que le llevan a cuestionarse precisamente los fundamentos de este tipo de gráficos cuando precisamente la realidad con la que se encuentra parece ir suficientemente en contra.

Descartar sectores como Energia, Telecomunicaciones o financiero parece tan fácil ahora como complicado luego en la práctica cuando uno se encuentra una época por ejemplo como los 70 donde tener una amplia presencia en el sector energía fue la forma de precisamente obtener una rentabilidad neta de la inversión en renta variable ajustada a inflación. Vamos que en los 70 quien hubiera querido vivir de rentas sin alterar el valor principal de su cartera ajustado a inflación, habría necesitado sí o sí este sector.

Luego está el problema de que decir de que sector es una empresa es más fácil a posteriori que a priori. Por ejemplo se considera a Amazon consumo cíclico pero yo diría que es una empresa que juega a muchos sectores en realidad. ¿Visa es sector financiero o tecnológico?

No sé hasta que punto empresas de unos sectores pueden quitar cuota significativa de negocios de otros sectores en teoría. Y tampoco sé como podrían actuar los que construyen índices ( o los fondos activos)ante la aparición de evidencias de este estilo.

Como ejemplo de fondo activo que en muchas ocasiones se vincula al sector consumo pero que en la práctica suele incluir mucho otro tipo de empresas: Colocación de activos|Los 10 principales activos|Robeco Global Consumer Trends D EUR|ISIN:LU0187079347

La tabla de correlaciones también es interesante.

No me atrevería yo a invertir en índices sectoriales… Mucho tendría que estudiarme el asunto.

Igual que los “tilts” a small cap value y similares que pasan años complicados. Parecen una tontería pero ese tipo de tilts ya requieren una convicción, autocontrol y educación financiera por parte del inversor muy alta.

El gráfico sectorial desde los 70s , invita mucho a la reflexión.

Uno podría pensar que tecnología sería el claro ganador…nada mas lejos de la realidad.

Incluso ,lo mas increíble es la relación rentabilidad-volatilidad .Los sectores menos volátiles ,son a menudo los mas rentables.

Gracias @agenjordi

Alguien dijo que una persona extraordinaria es una persona ordinaria que se plantea preguntas extraordinarias.

Admiro a quienes se cuestionan lo asumido por el consenso. Admito que no tengo contestación a sus preguntas. Podría decirle (y me quedaría la mar de tranquilo) que no hace falta pesar a alguien para saber que está gordo. Una compounder lo es hasta que deja de serlo. Y es que el futuro es siempre incierto e impredecible.

Podría contestarle diciendo un simple: No lo sé (y no me avergonzaría por ello).

Alguien dijo que invertir es fácil hasta que deja de serlo.

Para, enmarcar @Luis1 . Vd. postea lo justo,pero cuando lo hace,sus píldoras funden los plomos!

Gracias, por estar ahí.